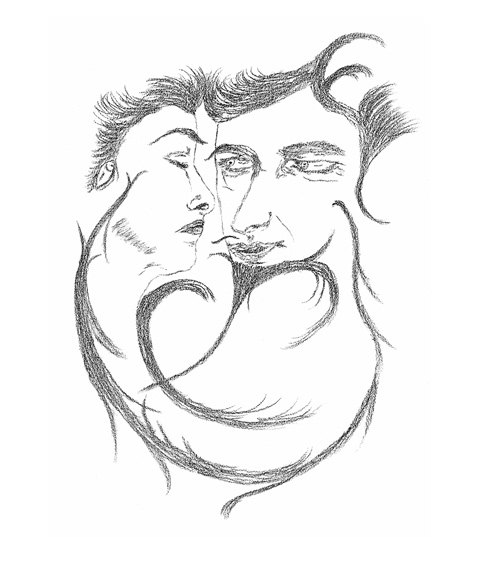

RAPSODIA (Rhapsody)

2005. Pencil on paper. 23x31 cm.

A couple in silent communication appears on the cover of the 2007 LOM edition of Rosenmann-Taub's Auge (Acme); their story refers to one of the poems in the book, “Rapsodia” (Rhapsody). The man and the woman were already parents, but their dream of having more children was dashed when she died while giving birth once again. The poem makes it clear that the tragedy happened a long time ago and that what remains of the event is only a distant memory: thus the characters in the drawing are beyond time and space. They no longer have bodies; only their energy endures.

Since they both are grief-stricken, who will bring solace to whom?

With a sadness that cannot be resolved, he gazes at her intensely. She has the same emotion but, absorbed in herself, she keeps her eyes shut.

The pair fell into the trap of wanting more. Now they are under the curse of remembering the consequences.

He still smiles slightly at the recollection of their former delights. He also wants to master his own pain in order to alleviate hers. There is only suffering for her, disappointment, and even repulsion (clearly visible in the down-turned mouth). She so much wanted her maternity to continue. What she loved the most was snatched away.

The swirling movements around them express his wish to comfort her, to reach out in an attempt at caresses — using his goatee, mustache, and eyebrow. The curved line of energy moving from his cheek all the way to her (and vice versa), evokes an abstract hand yearning to embrace.

Sweeping from him toward her, a wave brushes her throat. She responds with her beckoning eyebrow. They are directly touching only at the point where their hair lightly comes into contact.

In this process of fusion she has acquired some of his masculinity, and he some of her femininity.

Despite intensely experiencing their loss for eternity, they are composed: their closeness never changes.

“Rapsodia”, the poem, can be read below:

RAPSODIA

Elbirita ostentaba la costumbre

de sentarse de modo

que algunos (mequetrefes)

compañeros guindáramos

divisar

su secreto.

«¡Elvira!»

Ella no se movió.

«¡Elvira, por Dios santo!»

«Elbirita, con be

larga.»

«Párese al objetarme.»

«Llámeme usté

correctamente.»

¿Garrotes?

Unas lágrimas.

Todos (menos, muy pálida, Elbirita),

peñascal

de culpables.

El señor profesor no enristra dónde

catear. Se saca los anteojos. Toma

la tiza. «Un voluntario

que borre el pizarrón.»

¡Ayúdenme

a acordarme!

Cienbillones de siglos

o ayer: no queda nadie:

ni el señor profesor,

ni un compañero,

ni, por supuesto, yo;

ni Elbirita, quien, quizá me equivoco,

murió de pulmonía.

No, de parto.

Sí, sí, de parto, sí.

Tuvimos una niña; luego, un niño

y,

por cimera gloria,

aquel tenue embarazo de mellizos,

que, de un zarpazo, a ella le borró

su secreto

y a mí el campo de dicha.

Un voluntario, pronto, al pizarrón!»

RHAPSODY

Elbirita flaunted the habit

of sitting in such a way

that some of us (scoundrels)

classmates hoisted ourselves

to make out

her secret.

“Elvira!”

She did not move.

“Elvira, for God's sake!”

“Elbirita, with a b.”

“Stand up when you answer me.”

“Call me

by my right name.”

Cudgels?

Some tears.

All (except, very pale, Elbirita),

a rocky ground

of culprits.

The teacher does not master where

to peep. He removes his glasses. Picks up

the chalk. “A volunteer

to erase the blackboard.”

Help me

remember!

Hundredbillions of centuries

or yesterday: nobody is left:

neither the teacher,

nor a classmate,

nor, of course, I;

nor Elbirita, who, perhaps I'm wrong,

died of pneumonia.

No, in childbirth.

Yes, yes, in childbirth, yes.

We had a girl; then, a boy

and,

for supreme glory,

that delicate pregnancy of twins,

which, with one swipe, erased

her secret

and my own meadow of happiness.

“A volunteer, quick, to the blackboard!”